One of the most well-known comic duos in cinema history is Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. The odd duo’s chemistry was so strong that they appeared in four films together, the most notable of which were 1980’s Stir Crazy and 1989’s See No Evil, Hear No Evil.

Because Pryor and Wilder were the archetypal on-screen partners, many people imagined they were as close off-screen. The truth isn’t quite so straightforward. Pryor and Wilder were not adversaries, but their relationship behind the scenes, while courteous, was restricted to professional activities exclusively.

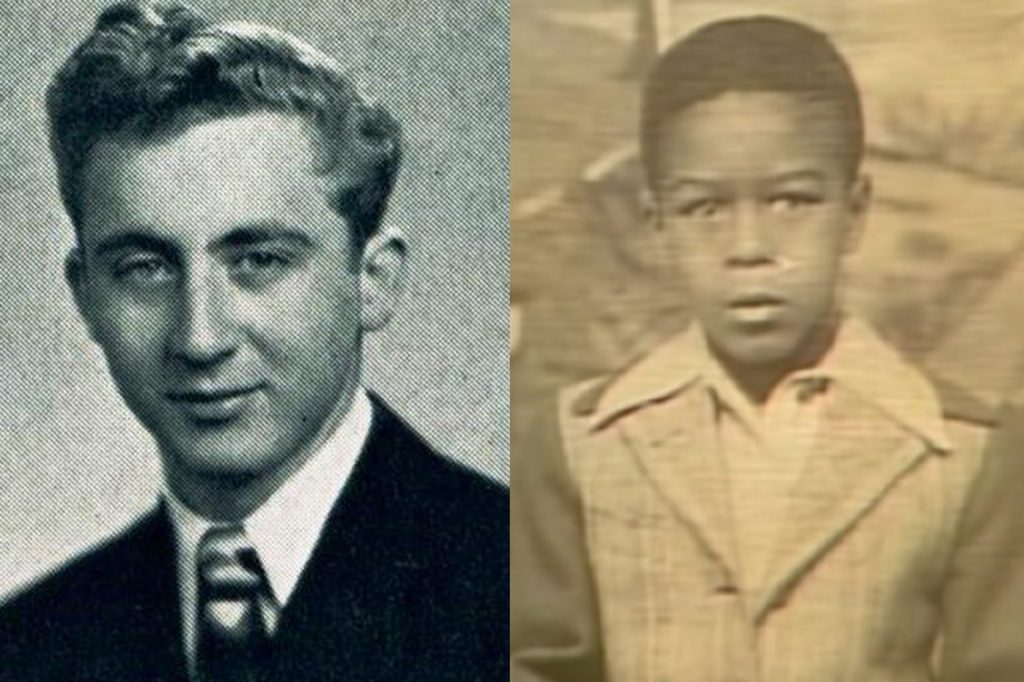

On June 11, 1933, Joel Silberman was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Richard Pryor was born in Peoria, Illinois, on December 1, 1940. Wilder was reared in a financially secure suburban environment, whereas Pryor was up in near squalor in a brothel owned by his grandmother.

However, both Wilder and Pryor experienced their share of adversity in their youth. Both suffered prejudice, Wilder because he was Jewish and Pryor because he was African-American, and both were subjected to severe bullying, including sexual assault.

Wilder began taking acting classes as a youngster and went on to study theatrical arts at the University of Iowa before moving to Bristol to train at the Old Vic Theatre School. When he returned to the United States in 1956, he joined the US Army and became a paramedic. In 1958, Pryor enlisted in the Army, but he spent the most of his two years of duty in military jail for fighting.

Both Wilder and Pryor began their careers in show business in New York in the early 1960s, Wilder as a Broadway actor and Pryor as a Greenwich Village nightclub funny. After working on a play with Anne Bancroft, she introduced him to her future husband, Mel Brooks, and the two men collaborated on The Producers, Brooks’ debut picture.

The Producers had mixed reviews upon its first release in 1967, but it pleased enough people to earn Brooks an Academy Award for Best Screenplay and Wilder an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Pryor got disillusioned with mainstream-friendly stand-up comedy about the same time, and significantly reworked his performance, making his gags considerably more personal, controversial, and explicit.

A match made in comedy heaven

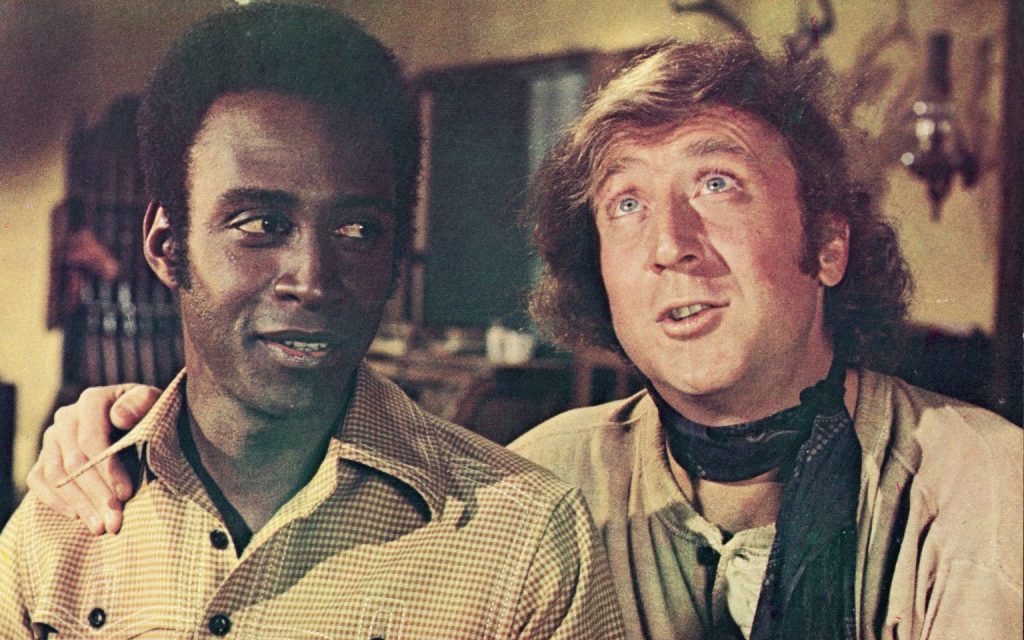

Pryor received an Emmy for his writing on Lily Tomlin’s TV show Lily in the years that followed, while Wilder starred in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (which, like The Producers, flopped on release but was later re-evaluated as a classic). Wilder and Pryor had never met before, but in Mel Brooks’ 1974 picture Blazing Saddles, their worlds clashed.

Brooks hired Pryor to co-write the western satire, and the director originally planned Pryor to play Sheriff Bart against Gene Wilder in the role of his Deputy, Jim. Unfortunately, Warner Bros. declined to cast Pryor due to his previous drug usage. In Pryor’s place, Cleavon Little was cast, and Blazing Saddles was a big success.

Pryor received an Emmy for his writing on Lily Tomlin’s TV show Lily in the years that followed, while Wilder starred in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (which, like The Producers, flopped on release but was later re-evaluated as a classic). Wilder and Pryor had never met before, but in Mel Brooks’ 1974 picture Blazing Saddles, their worlds clashed.

Brooks hired Pryor to co-write the western satire, and the director originally planned Pryor to play Sheriff Bart against Gene Wilder in the role of his Deputy, Jim. Unfortunately, Warner Bros. declined to cast Pryor due to his previous drug usage. In Pryor’s place, Cleavon Little was cast, and Blazing Saddles was a big success.

“Richard was a bad boy”

Silver Streak was a box office success, with reviewers and audiences agreeing that Wilder and Pryor were a wonderful comedic duo. Interracial humor was not unheard of at the time – Bill Cosby and Robert Culp co-starred in the 1960s TV series I Spy – but a black and white male coupling had never been paired together to such extent in comedy.

After that, it wasn’t long before Pryor and Wilder were paired up again in 1980’s Stir Crazy. It was even greater a hit than Silver Streak, and a substantial career boost for both men: Pryor became the first black actor to earn $1 million for a film part. It was directed by movie legend Sidney Poitier.

Things were less cheery behind the scenes, though, since Pryor’s drug usage was becoming a big issue. “Richard was a nasty child,” Wilder remembered in 2013. He’d arrive 15 minutes, 45 minutes, an hour, and an hour and a half late, which irritated us all. I didn’t say anything since I didn’t want it to end.”

Pryor was uncensored even at his best, and in an interview on the set of Stir Crazy, he stated flatly, “Gene Wilder ain’t s***,” among other colorful epithets. Given that Pryor was most likely inebriated at the time, it’s questionable whether he harbored any genuine enmity for Wilder.

Missed opportunities – and Pryor’s rock bottom

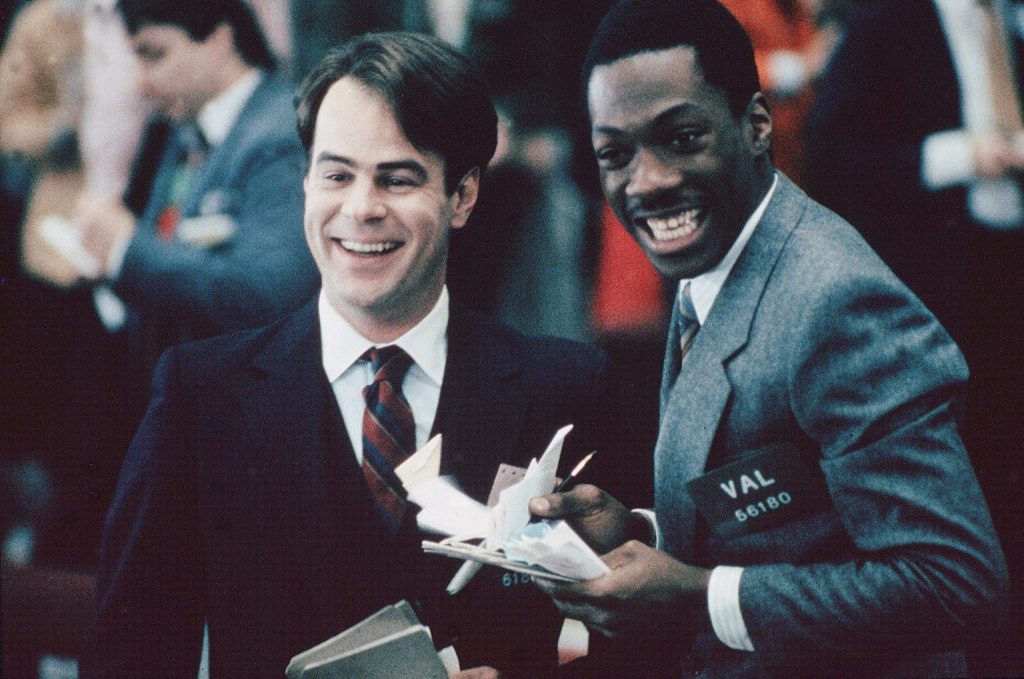

Before Stir Crazy was even finished, plans were already in the works for Pryor and Wilder to collaborate again, with a new project called Trading Places in the works. However, when Pryor was nearly burnt to death during a narcotics binge in June 1980, the brakes were quickly applied.

The specifics surrounding the event were not made known at first, and once Pryor had recovered, he used the incident to create jokes in his stand-up shows. Pryor would not admit to intentionally setting himself on fire in a suicide attempt until many years later.

Trading Places was released in 1983, featuring the newer, younger comic talents Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd, and movie was a huge box office success. Meanwhile, Pryor recovered both physically and professionally, starring in films like Superman III and Brewster’s Millions, while Wilder found success as both an actor and a writer-director with The Woman in Red.

Pryor and Wilder collaborated for the third time on See No Evil, Hear No Evil, over a decade after Stir Crazy (a reunion with Silver Streak director Arthur Hiller). In a sharp contrast to their previous partnership, Wilder praised Pryor’s performance on set, describing him as “an angel.”

Pryor and Wilder revealed in promotional interviews for See No Evil, Hear No Evil that they hadn’t seen each other since finishing Stir Crazy. Pryor, according to Wilder, is someone he would avoid socially because “I don’t want to risk having anything in my private life harmed.” I want [our relationship] to maintain the way it is so that the enchantment continues while we work.”

“I’m quite proud when I work with Gene… because I know I belong in this field,” Pryor said, expressing a similar emotion more bluntly. He also commended Wilder’s writing, noting that he took “an OK script and made it fantastic.”

“[Pryor] asked me once, when we were through with See No Evil, Hear No Evil, ‘why us?'” Wilder said in a subsequent interview. ‘What exactly is this thing?’ “Perhaps it’s best if we don’t find it out,” he replied as I opened my lips to respond. The chemistry between the two of them, according to Wilder, was nearly “sexual.”

Both guys were dealing with major personal issues by the time See No Evil, Hear No Evil was released in 1989. Gilda Radner, Wilder’s wife, died of ovarian cancer two weeks after the picture premiered. Meanwhile, Pryor has recently been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

Perhaps realizing that time was running out, Wilder and Pryor created their fourth and last picture, Another You, in 1991. Unfortunately, it was a sour note to end on: the production was problematic, and Pryor’s health was clearly worsening during the shoot. The film was a disappointment, and it is now virtually forgotten.

“The best comedy film friends of all time”

Another You not only ended their professional cooperation, but it also signaled the end of Pryor and Wilder’s careers in Hollywood, since they both generally retired from performing afterward. Pryor died of a heart attack in 2005, at the age of 65, after years of bad health. Wilder died 11 years later, in August 2016, at the age of 83, from complications related to Alzheimer’s disease.

“People frequently wonder. ‘Were Gene Wider and Dad friends?'” Pryor’s daughter Rain Pryor said on Facebook after Wilder died. ‘Not exactly,’ I usually said, ‘but they noticed each other’s brilliance and collaborated on successful pictures, and they were the finest comedic film pals of all time.’

“They to me, were the antithesis of how chemistry on film doesn’t always mean it translates off. Gene was a true grownup and I never saw him party. Dad was younger and we all know, he liked to party. The two together accepted the other.”

“They were distinct in natures,” Pryor’s daughter told The Hollywood Reporter. But there hasn’t been a spell like that in a long time in terms of his love and giving, and to witness the two of them together.”

Rain Pryor says that her father believed Gene Wilder “was fantastic… ” when asked about Richard Pryor’s genuine opinion about him. ‘That man’s a genius, and he’s a decent man, for sure,’ he constantly remarked.